Timber, Fish & Wildlife (TFW) Program

Updated 2/17/2022

Early Industrial Logging in Washington

Industrial scale logging and forest road building in western Washington state have a history that extends back to the mid 1800’s, prior to statehood, when settlers of European descent began to log shorelines, then rapidly moved inland, up river valleys and onto foothills. Technology used in timber harvest began with horse or oxen team and sled, moving to steam power, and onto modern diesel and hydraulic technology.

Most often, logging was conducted with efficiency as the primary goal, which meant speeding the greatest number of trees off of the hillsides towards log yards and mills for the least amount of cost, and with the fewest delays and injuries possible. Single clearcuts 1500 acres and larger are visible in aerial photos taken in the 1950s near Darrington. For many, many decades, much of the area logged in western Washington was not even replanted in evergreen species to reestablish forests but was allowed to naturally regrow with shorter-lived hardwood species.

Protection of soil, water, and streamside vegetation during logging was rarely, if ever considered. Often times, large volumes of logs were driven down streams and rivers, and rafted across lakes and bays, causing massive disturbance to bed, banks and shorelines. Trees growing next to streams, rivers and wetlands was harvested along with upland timber.

Logging roads and skid trails were built through steep and potentially unstable terrain, including across large pre-historic landslides that remain from the time that the Ice-Age glaciers retreated north. Timber on this type of terrain was routinely cut down and dragged to landings built on steep hillsides. Although landsliding is a natural part of the geology in Washington, these ancient landslides would sometimes begin moving again after logging occurred.

Heavy winter rain and spring snow melt were accidentally captured and then routed into streams and rivers by hastily built forest roads and skid trails, along with millions of cubic yards of sediment coming off of the road surface. Undersized culverts clogged by branches, gravel and other debris blew out, taking portions of road with them. Shallow rapid landsliding often occurred off of steep ridgelines that had been logged through.

1980's Rule Changes

By the 1980’s these historic logging and road building methods were generally recognized as harmful to fish and wildlife habitat and were understood to degrade clean water. Other events were happening that lead to a change in how logging and forest road building, known as forest practices, were conducted and permitted by state and federal regulators. One event was a 1974 federal court ruling that established the rights of Tribes in Washington state to catch up to 50% of the harvestable surplus of fin fish based upon federal treaties signed in the 1850’s. This ruling implied that Tribes have a vested interest in the intact habitat and clean water that produces the Treaty fishery, including habitat on forest lands.

Another event was the looming prospect of a federal listing of the Northern Spotted Owl under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), who’s range had been impacted by intensive logging of old-growth forests on state regulated and federal forests. An ESA listing of a species typically means that the federal government takes a more active role in regulating, and sometimes restricting activities that impact the listed species’ habitat. Finally, in the mid-1980’s, the timber industry began to face severe economic vulnerability in the state due to rapid changes in log export markets, unsustainable logging of certain timber sources, and the shuttering of domestic mills.

Recognizing the need to reform how forest practices were conducted in Washington state in order to protect the environment, respect Tribal treaty rights, comply with federal law, and sustain timber as a viable industry, multiple stake-holders assembled in order to figure out a way forward and negotiate a set of principles and a process for conducting forest practices. Stakeholders represented in the negotiations were tribes that had signed federal treaties, state government, timber industry, and a conservation caucus, representing various environmental non-profit organizations.

The outcome was the Timber/Fish/Wildlife Agreement, A Better Future in Our Woods and Streams, Final Report (TFW Agreement) released February 17, 1987. This document formalized agreement among stakeholders that a new regulatory structure for reviewing and permitting forest practices was required, laid out ground rules for cooperatively developing and implementing the rules, and identified specific elements that were to be included in the regulatory structure.

Although these rules were implemented to restrict activity on private land, it should be noted that they are designed to protect public resources.

Review of Proposed Forest Activities

Office Review

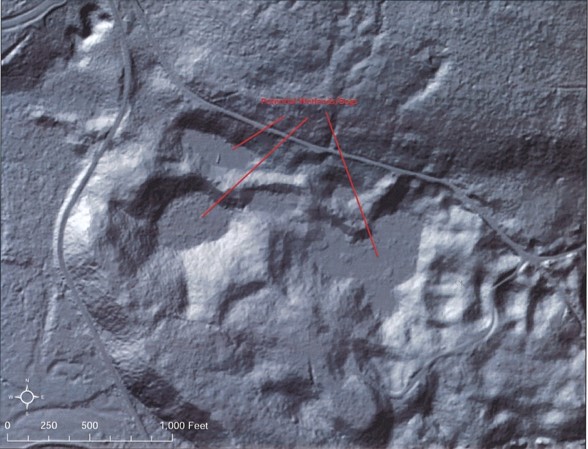

Prior to harvest, forest land owners are required to submit a Forest Practices Application that outlines proposed activities, identifies natural and cultural resources, and clearly defines how impacts to these resources will be avoided. A multistakeholder review process then evaluates the application for accuracy and adherence to the rules. A variety of tools may be applied in the office including, but not limited to, historical documents, aerial imagery, elevation maps, remote sensing (ex: LIDAR), and maps of documented resources. Any concerns or discrepencies are then communicated to the assigned Forester from the Department of Natural Resources for further evaluation and review.

Examples of aerial imagery and LIDAR used for office review (courtesy of Tulalip Tribes)

Field Review

If questions still remain after review of the paper application or if more information is needed, then stakeholders have the opportunity to visit the site of the proposal. These "Interdisciplinary Teams" (ID Teams) can then determine (1) if the application matches the reality of what is found on the ground, and (2) are there any additional threats to resources that could not be confirmed in the office. For example, a potentially unstable slope may or may not pose an imminent risk to resources but it is difficult to concretely determine the geology from aerial photos. A field visit allows professionals to come together and make better informed decisions.